Thursday 16th of October 2025 10:19 PM

The Tupac of Country Music

For over half a century there's been this debate, and one that's only intensifed and gotten louder with the passage of time, either about how country music started, by whom was it started, and what even is country music, really? Think the dust-up with Lil Nas X's honky-tonk #1 hit "Old Town Road" not being featured on the country billboard charts, and more recently Beyoncé releasing a fairly decent country album only to be shut out the CMA altogether.

Sure, some of it's cultural, and probably a little bit racíal even, but good sounds and artistic excellence cannot be easily denied, nor can the fact that country music was born right here in Mississippi, by soulful black folk previous subjugated to labor in the state cotton fields, before being picked up by poor whites in neighboring rural towns, and inevitably willed into an occupational way of life almost singlehandedly by one Jimmie Rodgers.

The specific definition of country music, according to Oxford dictionary, is: a form of popular music originating in the rural southern US. Traditionally a mixture of ballads and dance tunes played characteristically on fiddle, guitar, steel guitar, drums, and keyboard.

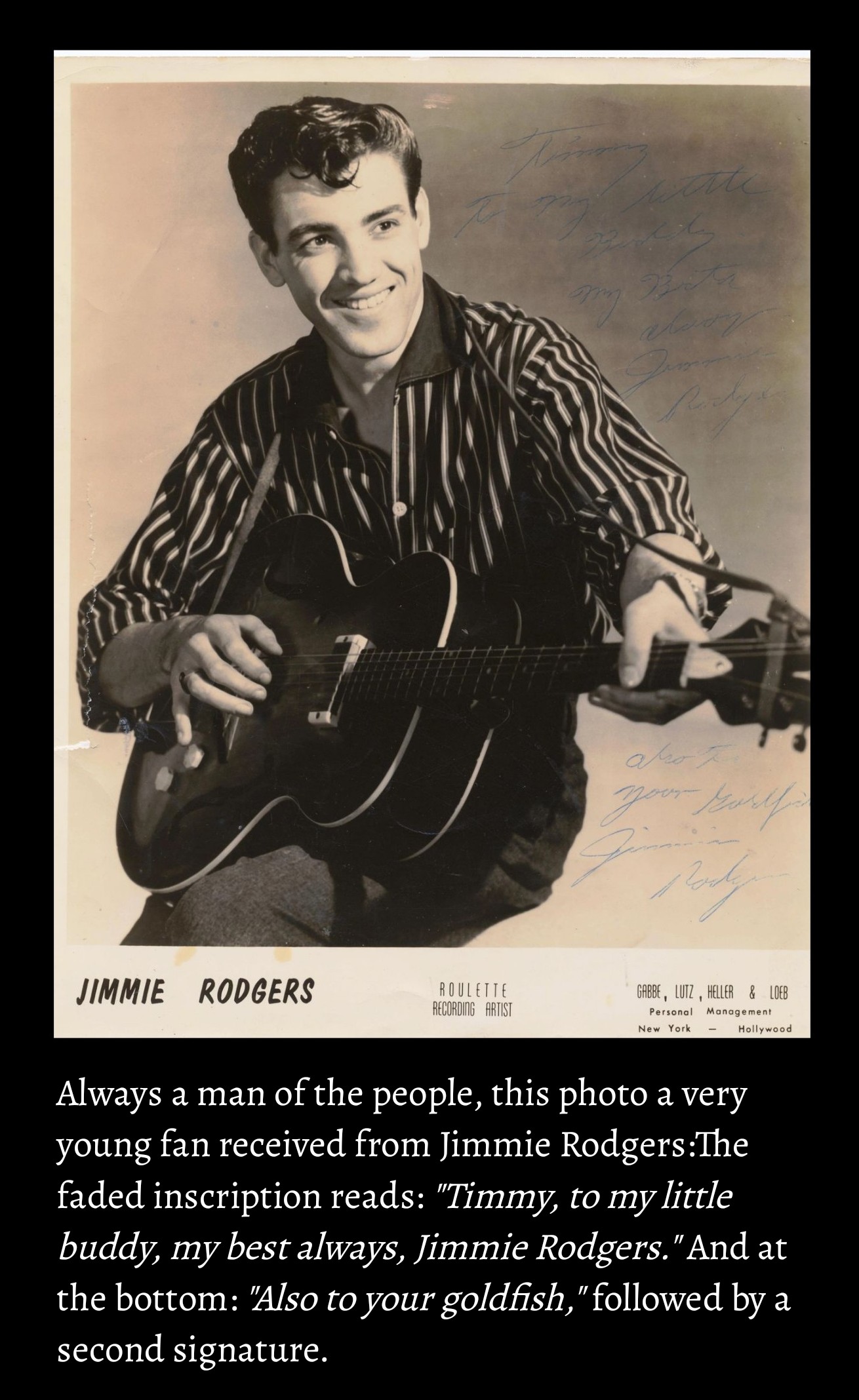

The acclaimed American documentarian director Ken Burns presents a comprehensive look at the history of country music in America and its evolution throughout the 20th century, in a film titled "Country Music." From its early years in the 1920s, when it was termed "hillbilly music," to the rise of bluegrass and rockabilly, the series also looks at how Nashville, Tenn., became the epicenter of the country music industry over the then-problematic Mississippi. Highlighting the connection between country music artists and their fans, the series concludes in the mid-1990s when a young Garth Brooks helps bring country music to a whole new level, but really and truly begins with Rodgers.

It was the Summer of 1927, and porch musicans and wannabes from across the Virginia Mid-Atlantic and Tennessee Valley regions flocked to Bristol in the Bible Belt, for a unique opportunity of a lifetime, which was short in those days, a rare chance to audition for the standalone Victor Record Company, a fairly major mover in 20th Century America's burgeoning music recording industry if for the simple fact that it knew the process when few others did. The seduction of a recording contract in those days was powerful like nothing else and attracted amateur singers and self-taught instrumentalists who were often part-time musicians occasionally managing local gigs some evenings but definitely doing full-time jobs as farmers, railroad and millworkers during the day. It was accepted as fact P.T. Barnum had made a fortune as the greatest showman of the time, and so many were eager to showcase their own talents in hopes of enhancing their dull reputations and earning the sort of cash that could help lift a few good hillbillies out of poverty.

Hence much of the music being made and played, primarily rooted in the southern folk traditions of Dixieland, was naturally labeled by supporters and detractors alike as "Hillbilly Hymns" or "Old Timie Tunes."

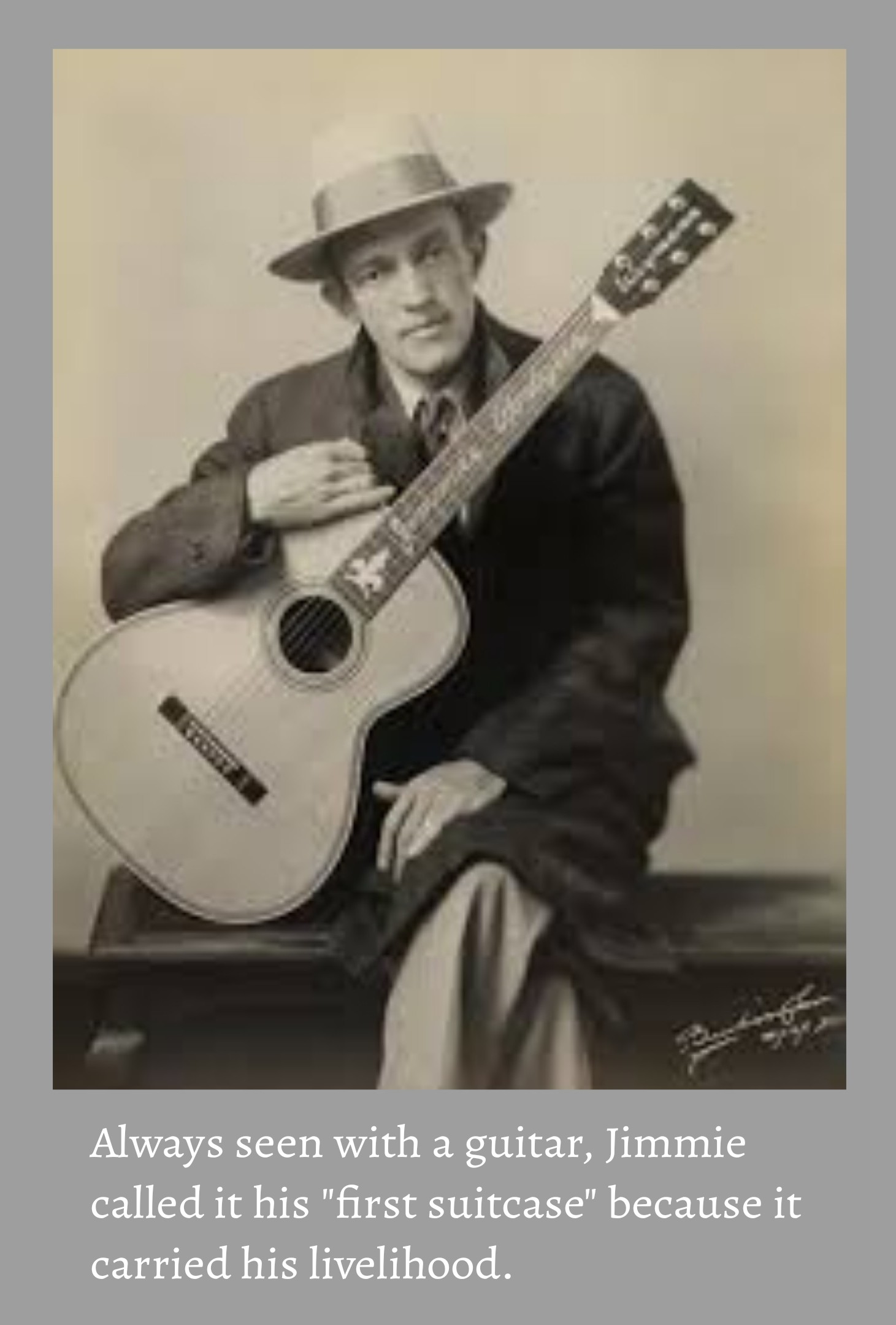

During this 10-day session structured like a solitary revival, Victor Record Company talent scout was a wiry man named Ralph Peer, who gave each aspirant less than three minutes to show him something and make magic happen in his ears. Among the tryouts was one Jimmie Rodgers, a Mississippi boy who wore his country bumpkin like a badge of honor and who would ultimately become a pivotal and fairly potent force in the formulation of country music from just a plantation past time that found its way onto the front porch into a billion dollar industry. If Peer liked you then he gave you extra time, and immediately he took to the sound of Rodgers, who recorded a couple poignant songs that day that would become staples in life: "Sleep, Baby Sleep," a traditional sounding lullaby that Peer loved, and "The Soldier's Sweetheart," a heart stirring ballad about loss in war that allegedly made the older man cry. Accompanied by nothing but a simple guitar that he would come to wear like an article of clothing, and a sincere, plain-spoken delivery, Jimmie impressed Peer more than anyone else that week and a half. However, Peer paid him five dollars less than the $20 promised, probably assuming it would be the last time he saw or heard of the poorly dressed kid who had hitched hiked all the way up from Mississippi and had more or less bartered for food the entire ten days.

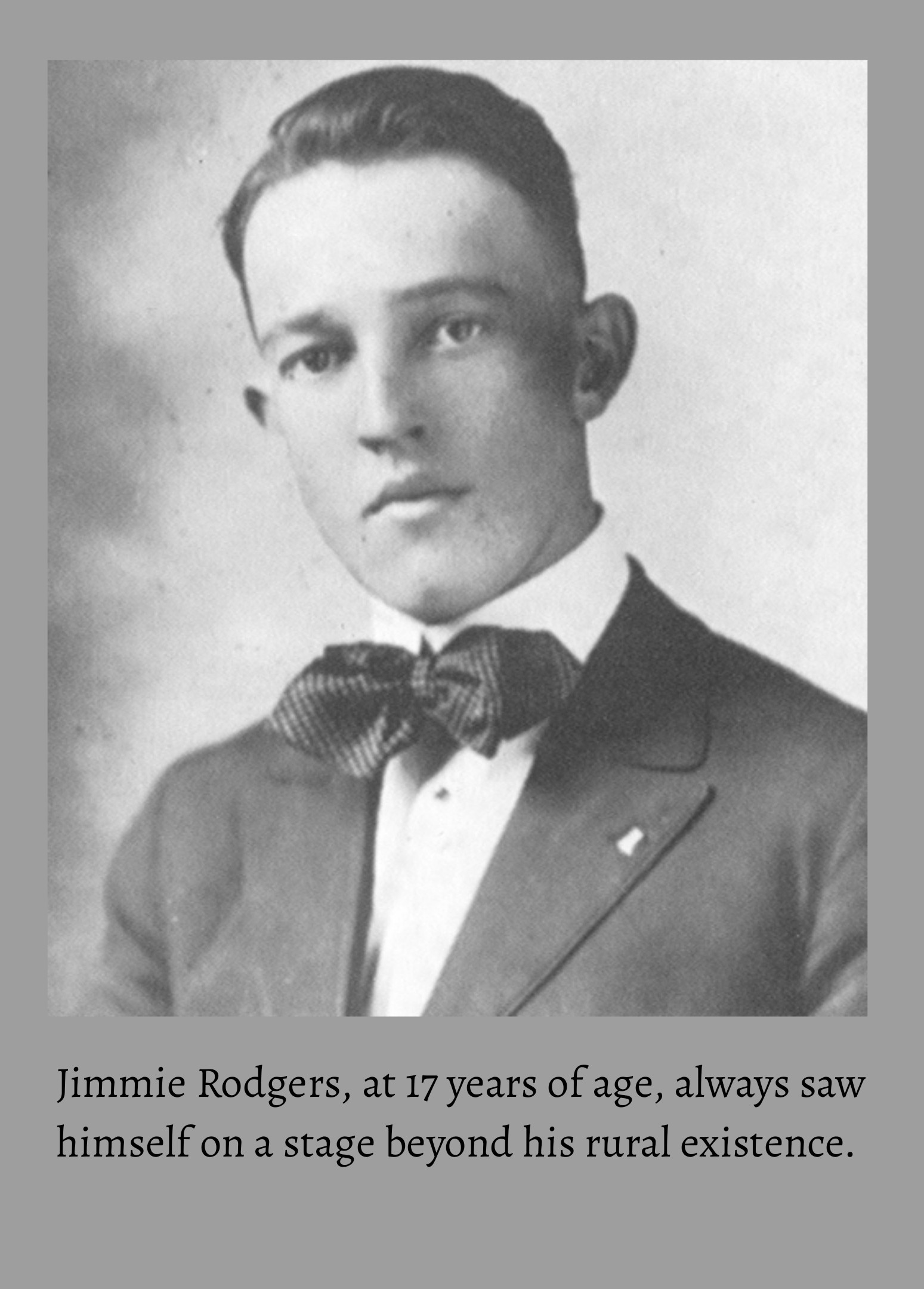

Rodgers, on the other hand, was changed that day of winning the money. Buoyed by the small success which he sold to everyone he knew as a stairway to stardom, he borrowed money from family and moved to the nation's capitol, where most successful music was ultimately submitted in the Library of Congress for recording keeping and also so he could have a direct train line to the NYC headquarters of Victor Record Co for future recording opportunities that arose. Before then, and to a much lesser extent after even, life had not been so kind to Jimmie Rodgers, whose various hardships included a laborious youth in the mills and losing his dear mother to early death from the then-common tuberculosis when he was just six years old, leaving he and his siblings in the challenging care of already burdened relatives while their father hustled endlessly for work on the railroads. While somewhat common, it was nonetheless a life that no boy wanted.

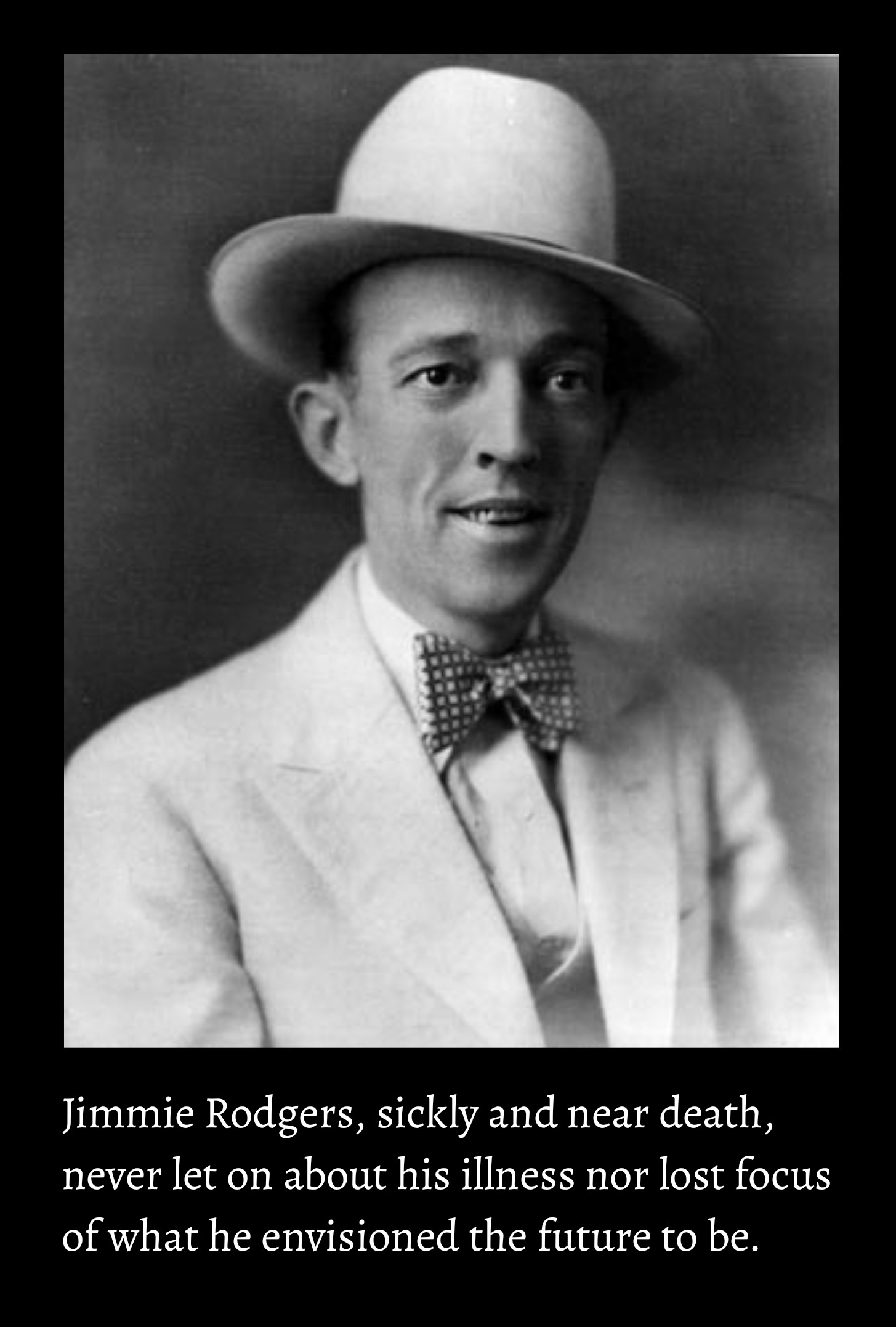

Nonsurprisingly Rodgers himself was also diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1924 and would spend his entire career battling that monster disease that he had literally watched snuff the life out of his mom, often saying part of his pursuit of music was because general railroad work made it difficult for him to simply breathe and he was not going to help the devil do his job, a spiritualistic claim he was not shy crooning about to audiences, since the same illness ravaged America proper in the early 1900s.

How Jimmie Found His Factor

Growing up in small town cotton Mississippi, Jimmie was drawn to the dark and dirty habits of the Delta, to the colorful and corruptible lives and loves and vices of rounders and gamblers and moonshiners, often found in saloons and barbershops and pool halls exhibiting the early characteristics of what's now known as the neighborhood rockstar lifestyle, never fearing his own demise yet still drifting in and out of various low-paying jobs with the mills and, yes, the railroads, living paycheck to paycheck while ceaselessly supporting the easygoing lifestyle he had become accustomed to, which included drinking and gambling and parlaying with an assortment of associates, an increasingly carefree attitude that contributed to the breakup of his first marriage to hometown girl Stella Kelly, with whom he had a brief and troubled union.

In spite of their divorce, Stella never stopped reflecting publicly on Rodgers' youthful charm and disarming immaturity that won her over in the first place.

In his teen years was when Jimmie Rodgers discovered the illícit and vibrant world of vaudeville, where singers and dancers and comedians and showmen all mixed and managed to capture his imagination in a way unparalleled. The spell of this environment propelled him to start playing ukulele chords, banjos, and eventually the guitar until he perfected it and inevitably immersed himself in music. So passionate, he was, that he played and practiced his sound with Southern blacks working on the railroads, and coincidentally absorbed their musical influences into that of his own, which significantly helped shape the Jimmie Rodgers style of singing.

By the Summer of 1920, Jimmie married a young woman named Carrie Williamson, the daughter of a local Pentecostal preacher who vowed to sear Satan out of the seemingly aimless Rodgers. Their love story was tumultuous; the two often wandered the south in search of work—and to get away from the preachy Williamson Sr—settling down only to uproot and go again as opportunities dwindled. In the face of these challenges, Jimmie was oft both a doting husband and devoted father, showering his wife and children with love and attention despite recurring financial instability.

By 1923, a severe bout of tuberculosis struck Jimmie and would lead to the diagnosis that most threatened his life. As mentioned the illness was arguably the leading cause of death early in the previous century, and, though he often sang about it, Jimmie's stubbornness to medically ignore his condition only worsened his health standing. After a brief stint in a charity hospital, he realized once and for all that drastic changes in lifestyle were past due, and so he cut back dramatically on devil-may-care existence and slid head on into the controlled world of entertainment, joining a relatively stable touring tent show.

No serious surveyor of music would call Jimmie Rodgers the most technically proficient musician and singer, but he possessed the unique ability that few did, or do to this very day, to connect with audiences with nothing but his voice over a few plucked strings, nothing else, via a totally relaxed delivery and innovative yodelling style. Utilizing diverse influences, Jimmie Rodgers blended black musical traditions with white sounds summarizing for the times fairly scandalous stories, bridging hard racial divides in a segregated America. The blend didn't just help propel yodelling into pop culture but also actually laid the groundwork for a new genre that appealed to both white and black audiences, when it actually began to be called "Country Music."

Still, even after embarking on his professional music journey, Jimmie Rodgers never stopped suffering poor man's struggles, often returning to the hated railroads because it was the only work that supported his family while leaving him time to figure out the best music monetization portion of least resistance. By 1927, however, he finally began to gain traction in the world of musical entertainment after a successful recording session with Ralph Peer that saw him summon his breakthrough song "T for Texas," a sneaky hit that showcased to the world at large his distinctive drawling style and helped solidify his place in the great music hall of fame.

Meanwhile, Jimmie's health continued to deteriorate despite his newfound success, often forcing him to cancel performances and mismanage the demands of fame not uncommon among celebrities across eras. When the Great Depression hit, the problems only compounded, though here Rodgers did better than most since his music was akin to a soundtrack for the battling man.

Like greats are known to do in those final years when sensing death's approach, Jimmie produced arguably his most remarkable body of work in spite of his fast declining health. His last recording session, in the Fall of 1933, revealed a man determined to leave a legacy beyond life. Tragically, though not surprisingly, Jimmie Rodgers passed away at the young age of 36, alone in a hotel room, like a Nikola Tesla, or a Kurt Cobain minus the obvious self-infliction, and still relatively poor financially like the story of too many greats across the genres and generations after him. But not before having a profound impact on the music industry in a way that only too few do.

Jimmie Rodgers is to country music what Tupac Shakur is to the genre of hip hop, because like Pac, Jimmie died struggling variously and often mightily in the vein of youthful ambition yet at the very pinnacle of his profession artistically. Like Pac, his music transcend regional and cultural boundaries, in life but probably more so in death, resonating with listeners Southward and beyond these great borders Jimmie Rodgers' eclectic mix of sentimental ballads, railroad songs as well as risque blues and Dixie novelty tunes appealed to a broad range of humanity, cementing his singular status as a pivotal pioneer of country music, and in the process making him the manifestation of a demigod. Again, like Pac.

Ultimately, Jimmie Rodgers' story is one of triumph over tragedy and adversity fairly advertised as one of the greatest stories ever told. Nearly a century after his passing, his songs continue to be sung and celebrated across communities as well as the country music establishment alike, proving that artistry at its most authentic is most amplified by its endurance. Jimmie Rodgers' legacy is not simply musical but societal in the way he bridged gaps and brought together groups through the universal language of song.

Always an inspiration to me, I'm proud to call Jimmie Rodgers my Mississippi homeboy.

Tags: Tracing the Legacy of Jimmie Rodgers, The Tupac of Country Music, Mississippi music, Country Music orgins, the founder of country music

More from DixieDigest